by Brian Grimmett, Kansas News Service

Wichita, Kansas — As global carbon dioxide emissions break records, Kansas is headed in the opposite direction — reducing emissions for 10 straight years.

Kansas’ decline is largely due to the rapid adoption of wind energy and a slow move away from coal powered electricity. That is to say: Kansas produces less carbon dioxide, or CO2, the powerful greenhouse gas that’s released into the atmosphere when we burn fossil fuels and is a major driver of climate change.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Agency, Kansas emitted 58.2 million metric tons of CO2 in 2017. That’s good enough to make Kansas only the 31st largest emitter in the U.S.

While it’s below the national average, on a global scale: “Kansas, if it were its own country, would be one of the top 60 CO2 emitters,” said Joe Daniel, an energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

So, when Kansas sees a reduction in emissions like it has in the past decade, it matters, he said.

The decline began in 2007, when total CO2 emissions in Kansas peaked at nearly 80 million metric tons.

Where CO2 comes from

So how did the state reduce its annual CO2 emissions by as much as the entire country of Bolivia so quickly? Three graphics explain it all.

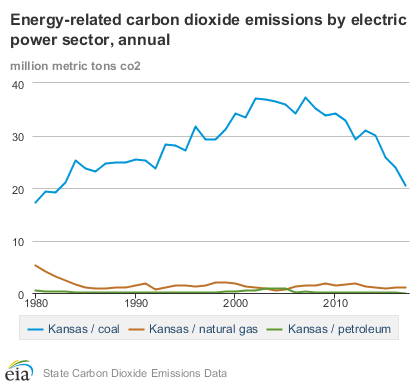

First, it’s helpful to know the source of Kansas’ CO2 emissions. In 2017, about half of total CO2 emissions came from burning fossil fuels, such as coal and natural gas, to create electricity. The rest was mostly from burning gasoline and diesel in our cars and trucks.

The recent reductions aren’t transportation-related, because, despite more efficient and cleaner burning engines, additional people and cars have offset the difference. In fact, total transportation emissions in Kansas have barely changed in the past 40 years.

That leaves electric power generation.

The decline of coal

As the graph shows, energy-related CO2 emissions began to plummet in the mid-2000s. Specifically, it’s emissions from coal-fired power plants.

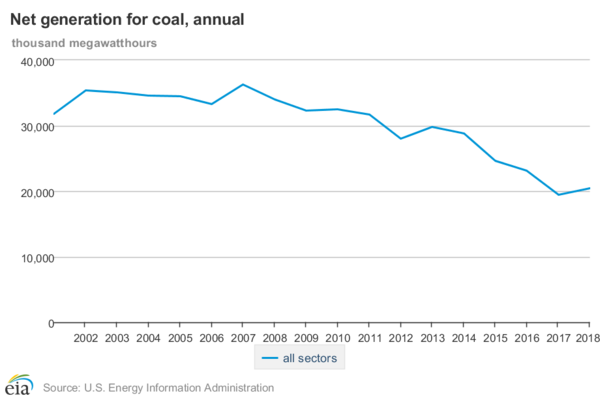

While some of the reductions are likely due to plant upgrades and federal environmental regulations that forced coal plants to clean up what was coming out of their smoke stacks, it’s mostly because plants burned less coal.

Coal plants in Kansas only produced about 20,000 megawatt hours of electricity in 2018, compared to an average of about 35,000 megawatt hours during the 2000s.

Daniel said the decline is largely due to economics. With the fast growth of cheap wind-generated electricity in Kansas, it’s become less profitable to run coal plants.

“I don’t think a month has gone by where I haven’t read a study about the poor economics of either coal plants, or coal mines, or the companies that invest in those properties,” Daniel said.

The rise of wind

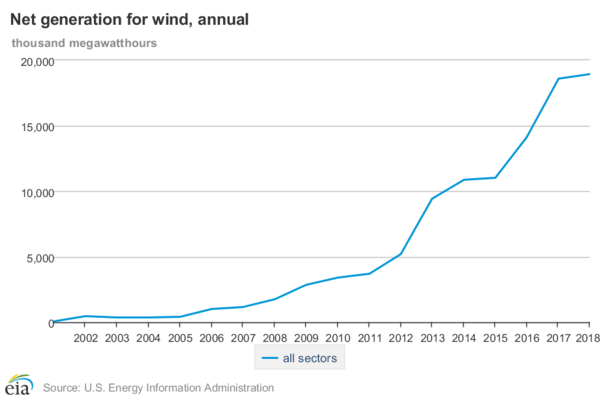

About 36 percent of all electricity produced in Kansas is from wind, the highest percentage of any U.S. state.

Twenty years ago, there was no such thing.

Part of the rapid growth of the industry is obvious: You wouldn’t put a wind turbine in a place with no wind, and there’s a lot of wind in Kansas.

Plus, federal and state tax incentives encouraged developers to jump into the market.

And it’s increasingly cheaper to build a wind farm.

Just this year, Kansas saw four new wind farms come online, adding enough capacity to power 190,000 homes for a year.

“Will we see four wind projects come online every year for the next five years? No,” said Kimberly Gencur-Svaty, director of public policy at the Kansas Power Alliance. “But I do think we’ll probably continue at a pace of where we’ve averaged the last 20 years, which is a project or two.”

How low can it go?

Ashok Gupta with the Natural Resources Defence Council said the move to renewable energy and subsequent decrease in CO2 emissions will be vital to reducing the impacts of climate change.

But, he wondered if it will be fast enough, especially in states that have a lot of wind.”

“We should be going by 2030 to pretty much carbon-free electricity,” he said.

While some states like Colorado have begun to adopt 100 percent renewable energy goals, Kansas has not. Even if Kansas were to get to 100 percent renewable energy, there’s still the nearly 20 metric tons of transportation emissions to worry about.

Achieving a clean electrical grid will also be key to reducing those emissions, Gupta said, even if it also means another, different shift in the way things are currently done.

“We have to start making sure that our transportation and our buildings are moving to all electric,” he said. “That’s the strategy for the next 10 years.”

Brian Grimmett reports on the environment, energy and natural resources for KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @briangrimmett or email him at grimmett (at) kmuw (dot) org. The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.

See more at https://www.kcur.org/post/heres-why-kansas-co2-emissions-are-their-lowest-level-40-years.