by Luke X. Martin, Kansas News Service

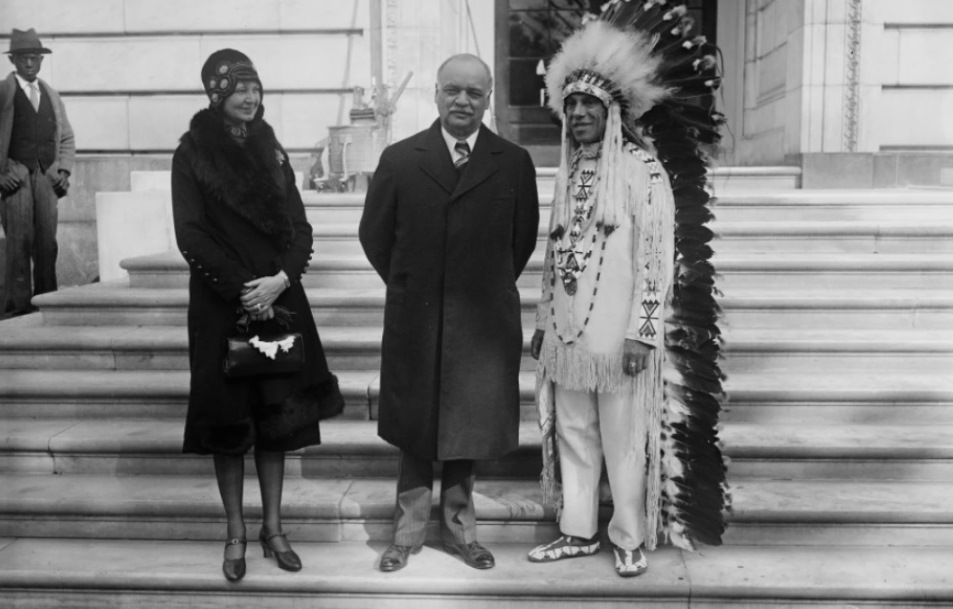

Charles Curtis was a leading voice in the fight for women’s suffrage. He also orchestrated the breakup of tribal government and communal land in what is now the state of Oklahoma.

When Vice President-elect Kamala Harris takes the oath of office on Jan. 20, she will be the first woman, first South Asian and first African American to fill the role.

But she won’t be the first person of color.

That title belongs to a Kansan — Charles Curtis, member of the Kaw Nation and President Herbert Hoover’s vice president.

Curtis was born in 1860 in Topeka while Kansas was still a territory, and he spent his early years living in both white and Native American communities.

His mother, Ellen Pappan, was one-quarter Kaw, and was the great-granddaughter of White Plume, a chief who offered assistance to the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1804, according to Curtis’ U.S. Senate biography. Pappan died when her son was 3 years old.

His father, Orren Curtis, a white man, fought in the Civil War and had a reputation for drinking. He was eventually dishonorably discharged from the Union Army and court martialed for killing three prisoners.

“He’s always remarrying, divorcing, gone fishing, gone to the army, and he’s just gone,” says Kansas historian Deb Goodrich, who is working on a book about Curtis’ life.

Before he spoke English, Curtis learned French and Kansa from his mother and her parents, whom he lived with on a Kaw reservation in Council Grove, Kansas, after her death. Despite the harsh conditions there, Curtis loved life on the reservation.

But Kansas was in turmoil. It was just emerging from the Bleeding Kansas era, and the Plains Indian Wars were in full bloom, says Goodrich.

In 1873, the Kaw were forced to move from Kansas to what is now Oklahoma, and Curtis had a choice to make: Go south with his maternal grandparents or return to Topeka and live with his father’s parents.

The decision, Goodrich says, was largely made for him: Go back to Topeka, get an education, and make something of yourself, his grandmother told him.

“I took her splendid advice and the next morning as the wagons pulled out for the south, bound for Indian Territory, I mounted my pony and with my belongings in a flour sack, returned to Topeka and school,” Curtis said later, according to his Senate biography. “No man or boy ever received better advice, it was the turning point in my life.”

Back in Topeka, Curtis worked hard and studied hard, and the political proclivities of his fraternal grandmother began to rub off on him, according to Goodrich.

“His Grandmother Curtis was described as a staunch Methodist and a staunch Republican, and they weren’t sure which one was the strongest,” Goodrich says. “They had a big family and she brought a lot of votes to the table.”

By 1881, Curtis had been admitted to the Kansas Bar and began practicing in Topeka. Three years later, at the age of 24, he was elected Shawnee County attorney, where he took a hard line enforcing the state’s prohibition laws.

Reflecting on a political tour he took with Curtis in 1891, journalist William Allen White said he’d never met anyone who could charm a hostile audience as effectively. White also noted Curtis’ way of remembering all the Republicans in each town, using a little book that he filled with all their names.

Curtis made the jump to national politics in 1893, winning a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and serving seven terms.

As a Congressman, he crafted and navigated the Curtis Act of 1898 through Congress and into law. It was his most lasting legacy as a lawmaker, according to Goodrich.

“The Curtis Act, unfortunately, was a death knell to the tribal sovereignty for many of the American Indian tribes,” she says. “And I don’t think that Curtis meant it that way, but he also believed in assimilation, because this is how he had survived.”

The law abolished tribal governments, broke up communal lands and allowed members of the Dawes Commission in Washington, but not tribes themselves, to determine who was and who was not a tribal member.

“It’s one of those ironies that Natives were not considered citizens and that dissolving the tribal sovereignty was a step in making them U.S. citizens,” Goodrich says. “And that’s just one of the great tragedies of our republic.”

Curtis served two terms in the U.S. Senate, first appointed to the post by the Kansas Legislature in 1907 and serving until 1913, when Democrats took control of the Statehouse.

With the passage of the 17th Amendment, which allowed voters to elect Senators directly, Curtis was sent back to Washington in 1915 and he served 14 more years.

While in the Senate, Curtis served as Senate president pro tempore, minority whip and Republican majority leader. He also led the Senate floor debate for the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.

“He definitely championed women’s suffrage, and he was very proud of that,” Goodrich says. “And one of the Washington correspondents famously said, ‘Charlie can never be accused of being a progressive, but the feminists considered him their friend.'”

Idaho Sen. William Borah called him “a great reconciler, a walking political encyclopedia and one of the best political poker players in America.”

It would be more than 63 years before another Native American, Colorado’s Ben Nighthorse Campbell, served as U.S. Senator after Curtis resigned in 1929 to become vice president.

Though Curtis had long held presidential ambitions and worked hard behind the scenes to make it happen, his rise to the upper echelons of the executive branch was ultimately unsatisfying.

At the Republican National Convention in 1928 at Kansas City’s Convention Hall, Curtis was paired up with Hoover. It was on odd pairing, considering the two had been at odds since at least 1918, when Hoover had campaigned for Democratic candidates.

That tension extended through their time in the White House, although Curtis spent little time there, according to Goodrich, and largely neutered his ability to get anything done.

“The joke at the time was that if Curtis wanted to go to the White House, he would have had to buy a ticket on one of the tours,” she says.

The Hoover-Curtis ticket lost its reelection bid in 1932, three years into the Great Depression, to Democrats Franklin Roosevelt and John Nance Garner.

Having been fully ensconced in Washington’s political scene for decades, Curtis stayed there after his term ended and practiced law. He died of a heart attack in 1936 and was buried at the Topeka Cemetery.

“I do think that Charles Curtis has mostly been forgotten,” Goodrich says. “I think part of that is he was in an administration as vice president that people wanted to forget.”

Not everyone, though, wants to forget. In 1993, Donald and Nova Cottrell purchased Curtis’ former home in Topeka.

“It was actually slated to be demolished by the city because nobody was interested in purchasing the building,” Nova Cottrell told C-SPAN in 2015.

The Charles Curtis House Museum, at 1101 SW Topeka Blvd. in Topeka, is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Luke X. Martin is a reporter focusing on race, culture and ethnicity for KCUR 89.3. Contact him at luke@kcur.org or on Twitter, @lukexmartin.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on the health and well-being of Kansans, their communities and civic life.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to https://ksnewsservice.org/.