by Lily O’Shea Becker, Kansas Reflector

Fifty-two percent of Kansas food pantries reported serving more clients in 2021 than 2020, according to a new study from the University of Missouri.

This trend is nationwide, as food pantries are experiencing an increased need in food assistance because of inflation and lingering effects of the pandemic. In Kansas, the situation could soon get worse.

In April, the Kansas Legislature overrode Gov. Laura Kelly’s veto of House Bill 2448, which will require adults without dependents to complete an employment and training program in order to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program assistance, formerly known as food stamps, starting July 1. The law will only apply to those ages 18 through 49 who work fewer than 30 hours a week.

“This new study that just came out actually shows that people are working, and that at least one person in the home was working, and it’s really difficult,” said Joanna Sebelien, chief resource officer of Harvesters. “And many of them had full time jobs as well. And, yeah, the amount of money they’re making is basically below the poverty level.”

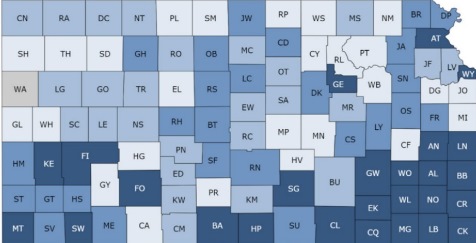

Harvesters is a food bank that serves 26 counties in northwestern Missouri and northeastern Kansas. The organization testified in opposition to HB2448.

SNAP benefits are available to households whose incomes meet or are below 130% of the federal poverty guidelines. According to the study, 79% of Kansas households are eligible for SNAP based on their income, but only 31% of food bank clientele households have used the food assistance program within the previous year.

Harvesters attributes the lack of SNAP participation to state policy barriers, such as HB2448 and a series of bills passed in 2015 and 2016 called the HOPE Act. Between 2015 and 2020, SNAP enrollment dropped approximately 25%.

“The pandemic did bring more hunger and hardship to Kansans,” said Haley Kottler, the anti-hunger campaign director for Kansas Appleseed. “And so we really have seen food insecurity heightened over the past couple of years. But what I do want to say is programs like SNAP are there to help mitigate this. And so when the pandemic began, the food insecurity projections looked a lot higher than they actually ended up being because of programs like SNAP and Child Nutrition Programs.”

Seventy percent of Kansas food pantries reported serving more clients affected by COVID-19 in 2021 compared with 2020, the University of Missouri study shows.

Food insecurity in Kansas rose from 12.1% to 14.1% in 2020, according to Feeding America. As the biggest food assistance program in the country, the Kansas SNAP program alone has triggered approximately $164 million in economic activity since the beginning of the pandemic. As food insecurity grew, SNAP participation declined, according to Harvesters.

But enough Kansas legislators supported HB2448, model legislation brought to Kansas via an out-of-state lobbying organization, to override Kelly’s veto.

“What is the central solution to poverty? It’s work. Work is not a punishment, it’s a blessing,” said Rep. Susan Humphries, a Wichita Republican, as she argued in favor of the bill. “Helping someone move to a place of self-sufficiency is a gift to them. Work, not money, is a fundamental source of dignity, and getting that training that will move them there is a process to hope and self-respect.”

According to the University of Missouri study, of the Kansas households that utilize food banks, 60% have at least one working adult, 34% have at least one person who is working full-time, and 47% make $15,000 or less per year. Forty-one percent of these households choose between paying for food or medicine and medical care within the last year, and 49% choose between paying for food and utilities.

“I think (the University of Missouri study) shows that the people who are food insecure are people that you might not think, so many people think it might be an urban problem, or it’s an ethnic problem, but it’s not,” Sebelien said. “I mean, it shows we serve a very diverse group of people — Caucasians, Hispanics, African Americans, and other groups as well. And, you know, children and seniors.”

Of the food bank clients who were surveyed, 62% identify as white, 13% identify as African American, and 18% identify as Hispanic, according to the University of Missouri study. People of color experience higher rates of food insecurity. Families living in Indigenous communities are two times more likely to experience food insecurity compared with their counterparts, according to Harvesters. Nine percent of clients reside in temporary housing or are houseless.

“I cannot support a bill that makes it more difficult for Kansans to feed themselves, particularly when prices at the grocery store are increasing,” said Rep. Tom Sawyer, a Wichita Democrat. “Thirty thousand hardworking Kansans will be affected by this, including families and those with children. I will not vote for a policy that makes it harder for children to grow and thrive in Kansas.”

According to Feeding America, one in eight Kansans face hunger, and one in six children in Kansas face hunger. The reality is more stark in regions like southeast Kansas, where one in four children are food insecure.

On Wednesday, the governor sent a letter to Congress requesting they extend the federal Child Nutrition Waivers, which were put in place at the beginning of the pandemic to guarantee students access to free meals during the school year and summer. These waivers have provided meals to 30 million students across the country. The waivers are due to expire on June 30, and if they are not extended, approximately 10 million students will be affected.

Food insecurity is not solely experienced by families. The University of Kansas Campus Cupboard is a food pantry that aims to reduce food insecurity among KU’s campus community. According to the study, 82% of food pantry clients in Kansas have a high school degree or higher level of education.

While the pantry is available to students, faculty, staff and affiliates, the pantry estimates the majority of its clients are students.

“This past academic year, we had over 3,000 visits to the Campus Cupboard,” said Sarah Ross, who oversees the daily operations of the Campus Cupboard. “I think a large part of that is because of the pandemic and inflation happening.”

SNAP eligibility rules differ for students in higher education compared to the general population. SNAP eligibility for higher education students expanded after The Consolidated Appropriations Act went into effect on Jan. 16, 2021, and is in effect until the end of the public health emergency is declared.

Kottler said Kansas Appleseed worked hard to encourage passage of House Bill 2215 and House Bill 2525. HB2215 would have reversed the ban on food assistance for Kansans with more than one drug felony. HB2525 would have reversed the ban on food assistance for Kansans who don’t cooperate with child support services. Neither bill passed this year.

To help Kansans determine their SNAP eligibility and navigate the Kansas SNAP application process, Harvesters established a SNAP Outreach program.

HB2448 goes into effect on July 1. Beginning in January, Kansans can expect some economic relief concerning food with House Bill 2106, which will phase out the Kansas sales tax on groceries. Kansas’ sales tax on groceries is the second highest in the country, at 6.5%.

Kansas Reflector stories, www.kansasreflector.com, may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.