Although more KCK residents now have insurance, lack of providers limits access to health care

by Alex Smith, Heartland Health Monitor

Editor’s note: A male in Wyandotte County can expect to live about seven fewer years than a male in Johnson County. A female in Wyandotte County can expect to live nearly six fewer years than her Johnson County counterpart. About 21 percent of Wyandotte County residents consider themselves to be in poor or fair health; fewer than one in 12 in Johnson County do so.

Those are just a few of the many health disparities that sometimes make the side-by-side Kansas counties seem like different countries.

This week’s “Crossing To Health” series explores that health divide and examines attempts to narrow the gap. Today’s story looks at the challenges that Wyandotte County residents face when accessing primary care.

On a Sunday morning, New Bethel Church in Kansas City, Kan., comes alive with the sounds of worship as a full gospel choir and band bring hundreds of congregants to their feet.

At the center of the action, guitarist Clarence Taylor sits with his eyes lowered, strumming angelic-sounding chords. Taylor has a sound that would put a lot of hot-shot guitarists to shame, but he doesn’t claim the talent for himself. He says it’s a divine gift.

“I don’t know the notes,” Taylor says. “I can just pick it up. Sometimes it amazes me.”

The 61-year-old owns a janitorial business, and his income can be unpredictable. For years, instead of buying health insurance and seeing a regular doctor, Taylor paid for health care out of pocket when emergencies arose.

But with the help of the church’s community health director, Broderick Crawford, Taylor was able to get subsidies and insurance and connect with primary care doctors and nurses to treat his diabetes and heart issues.

“God has hooked me up with the right people,” Taylor said. “So I’m glad.”

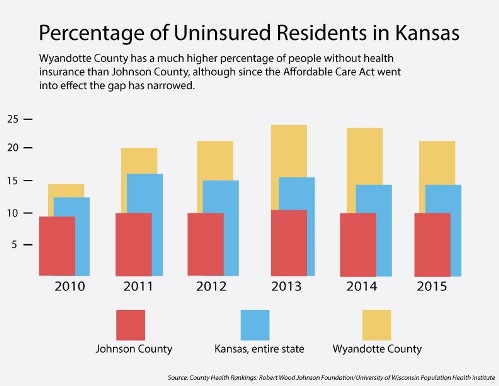

The “right people” can be hard to find in Wyandotte County. In the past couple of years, the Affordable Care Act has provided thousands of county residents with health insurance, creating a surge in demand for health care in a county that already was designated a health professional shortage area by the federal government.

Wyandotte County has just half the number of active primary care doctors per person as neighboring Johnson County, even though it’s home to the University of Kansas Hospital and the University of Kansas Medical School.

The heightened demand won’t suffice to lure more physicians. Rather, the future of the county’s health workforce is more likely to be shaped by the decisions of those fresh-faced medical students at KU Med about to embark on their careers.

Choosing a future

On a Monday evening at the JayDoc Free Clinic in Kansas City, Kan., second-year students are learning some of the basics of family medicine. They perform routine physicals, treat pain and, with the guidance of a supervising physician, address other health issues that patients report.

It’s an eye-opening experience for Adam McCann that will help inform a decision he’ll have to make soon: what kind of doctor he wants to become.

“It’s definitely something that’s on our minds from day one,” McCann said. “It’s just trying to delay the big decision until later.”

Family and internal medicine pay an average of about $190,000 a year. That’s a great living by most standards, but it’s at the bottom of the pay scale for doctors. Specialists in orthopedics or cardiology typically make twice as much.

And as students like Hailey Baker consider a debt load that averages about $180,000, the pay difference is hard to ignore.

“That is something I think about, because it is just insane how in debt I’m going to be,” Baker said.

Once students like McCann and Baker become doctors, money will likely play a big part in where they choose to work.

Private insurance pays doctors much more for treating patients than Medicaid or Medicare. With plenty of privately insured residents, Johnson County almost guarantees a good salary. Not so in Wyandotte County, where there are far fewer privately insured patients.

And that situation probably will only get worse as politicians and insurers try to rein in spiraling health care costs.

Student Maddy Breedan said that adds another element of uncertainty when it comes to choosing a career.

“It is a little bit worrisome sometimes, just with things changing so rapidly and kind of not knowing what the direction is,” Breedan said.

To lure more primary care doctors to Wyandotte County and other areas deemed medically needy, Kansas and the federal government have adopted loan forgiveness programs. And while these programs have attracted some doctors, the overall problem in Wyandotte County remains the same.

Higher calling

The solution, according to Erin Fraher of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, may be to appeal more to the heart.

“It’s not just about reimbursement,” said Fraher, an assistant professor and director of the Carolina Health Workforce Resource Center. “It’s about the quality of practice. It’s about the joy in practice.”

Fraher says medical schools need to get students out of the classroom and hospital, and instead working in communities like Wyandotte County as early as possible. Doctors can be inspired to a higher calling if there’re exposed to it before financial incentives take hold, he believes.

Photo by Heartland Health Monitor

“When they put their students out into these underserved communities, medical students become excited about serving these patients,” Fraher said. “We know then that they can pursue a residency in a community where there’s greater need.”

Sounds good in theory. But even for doctors who have a passion for it, the work isn’t easy.

“It’s a really tough way to make a living,” said Dr. Sharon Lee, who founded the Family Care Clinic in Kansas City, Kan., more than 25 years ago.

Many of the patients Lee sees have complicated health issues and challenging lives characterized by poverty, unremitting work demands, lack of transportation and emotional issues, among other problems.

It’s common for patients to simply fall off the radar.

“It feels very much like failure,” Lee said. “It’s hard when you have a person that you believe you have some way of helping, and then they don’t follow through. It’s hard.”

More than two-thirds of doctors who chose family medicine say they wouldn’t do it again, according to surveys conducted by the physician news source Medscape.

To support the work of primary care doctors, Fraher said communities need people to help patients after they leave the doctor’s office.

“You need to build a team around them,” she said. “You need social workers. You need community health workers to help translate what the physician says to the patient and help them be adherent.”

In fact, community health workers — often non-professionals who help coordinate care in their own communities — have become more common in Wyandotte County in recent years.

El Centro, for example, began enlisting volunteers in its Promotoras de Salud program in 2009 to provide outreach for Spanish-speaking residents.

And new grant funding, like last year’s award of $1.6 million to the Community Health Council of Wyandotte County from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, supports salaries for more of these workers.

Even so, the data suggest the mismatch between available doctors and patients is growing.

Wyandotte County’s ratio of primary care doctors to residents has worsened. Meanwhile, Johnson County’s has improved.

So even though Wyandotte County’s uninsured rate is falling and the county is providing more to help the newly insured, many residents likely will have an even harder time finding basic health care.

Clarence Taylor, the guitarist who received assistance through his church, said he can understand why that would leave residents feeling somewhat desperate. He remembers the sensation well.

“That’s when you really start praying,” he said. “Saying, ‘God, you’re gonna have to help me, ’cause I don’t know who to talk to.’”

— This article was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the National Health Journalism Fellowship, programs of USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism.

The nonprofit KHI News Service is an editorially independent initiative of the Kansas Health Institute and a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor reporting collaboration. All stories and photos may be republished at no cost with proper attribution and a link back to KHI.org when a story is reposted online.