In the turbulent years following the Civil War, around 27,000 former slaves migrated to Kansas. They called themselves “exodusters” and they were fleeing Jim Crow laws. Some of them are remembered in a portrait exhibition of an African-American community in Leavenworth, Kansas.

by Julie Denesha, KCUR and Kansas News Service

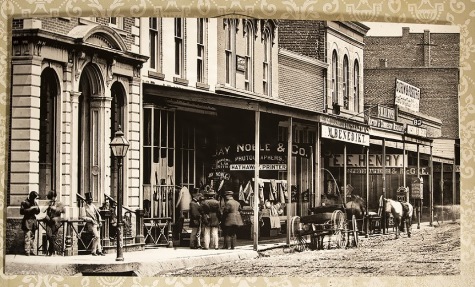

Photo studios were busy places in Leavenworth, Kansas, in the late 1870s. Thousands of everyday people flocked to have their pictures taken.

Today, some of those pictures have re-emerged — and they tell a story of an African-American community that took root in the town as Black families migrated to escape the Jim Crow south.

An exhibit on display at the Black Archives Museum in St. Joseph, Missouri, features a series of black-and-white portraits that have survived more than a century. (https://www.stjosephmuseum.org/black-archives-museum)

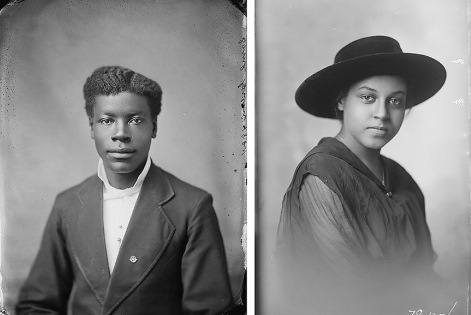

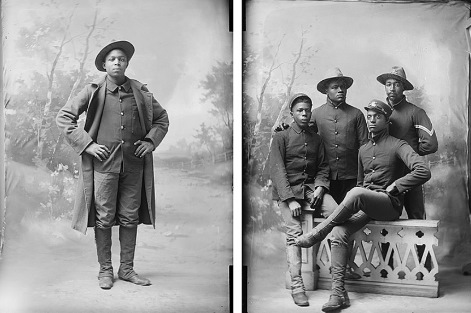

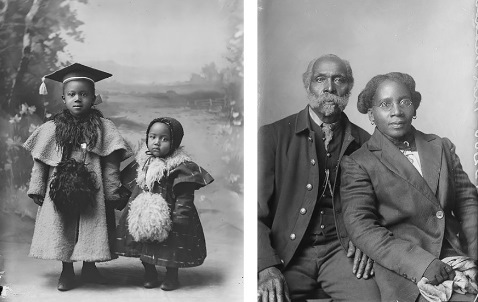

An older man and woman are decked out in their Sunday best. A quartet of soldiers poses in front of a woodsy backdrop. A young woman in a black hat looks boldly into the camera lens. All of the subjects are African-American.

Jade Powers, assistant curator of art at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, wasn’t involved in the creation of the exhibit, but she takes a special interest in highlighting artists and subjects underrepresented in museum collections.

“So often, the portrayals before were not maybe how African-Americans saw themselves or they were very political in a negative way to keep, you know, a certain status quo. And so with these images, it’s so exciting,” Powers said.

“I mean, you’re looking at couples, you’re looking at soldiers. It just really expands on the history of America.”

In the turbulent years following the Civil War, around 27,000 former slaves migrated to the land of John Brown. They called themselves “Exodusters” and they were refugees from Jim Crow laws and lynch mobs. Their journey came to be known as the “Great Exodus.”

“There seems to be a real interest from Black and Brown artists, to really look at historical figures and reimagine them or be able to uplift them in different ways,” Powers said. “I am not a practicing artist, but I imagine someone could have a field day with stories of these people taken from this historical narrative.”

The photos would never have come to the public eye if not for the persistence of Mary Everhard, a photographer who moved to Leavenworth in the 1920s.

Everhard had a keen interest in history. As older photographers closed their doors, she bought up their archives.

Eventually, her collection took up an entire room, floor to ceiling, 40,000 negatives in all. Everhard guarded them for years, through two tornadoes, a flood and a fire.

“It’s such an incredible story,” said Mary Ann Brown, a volunteer at the Leavenworth County Historical Society “It’s hard to know even where to start with Miss Everhard.”

Brown is part of a team that’s been scanning Everhard’s negatives since 1998. She considers Everhard a folk hero — the woman who preserved decades of early Leavenworth history. But people didn’t always appreciate Everhard’s efforts.

“When she decided to retire, she went to the local banker and she wanted to know what she could get for these negatives,” Brown said. “And he said, Miss Everhard, you might as well just throw these in the Missouri River. They’re not worth anything.”

Thankfully, the negatives escaped a watery grave. A collector from Chicago purchased them in 1967. He sold off parts of the collection to different museums.

One of them was The Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. Today the Carter keeps around 6,000 of Everhard’s negatives in temperature-controlled vaults. The portraits on display at St. Joseph’s Black Archives Museum come from that collection.

“Even though photography is often talked about as one of the more democratic art forms, that still took a certain amount of money and a certain amount of access and standing to have an image taken,” said Kristen Gaylord, the museum’s assistant curator of photographs.

“A lot of Black Americans didn’t have that right away after the end of slavery,” she noted. “So especially the 19th Century images, I would say, are unusual, which is why they’re so valuable to us.”

Gaylord sees Mary Everhard as a woman ahead of her time.

“Not only was she a successful female photographer at the time, but she’s also the one who saw the need to conserve all these negatives,” she said.

The Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, California, also acquired a portion of the Everhard collection. In the late 1990s, the Leavenworth County Historical Society raised the funds to purchase 25,000 negatives from the Autry and return some of the images to the city where they started. They form the heart of the historical society’s photography collection — the one that Brown and fellow volunteers have been working on for years.

Thanks to Mary Everhard, the Chicago collector and those volunteers, the images that could have landed in the Missouri River now tell a story about early Leavenworth and the people who called it home.

And the exhibit at the Black Archives Museum in St. Joseph tells us that the story includes former Black residents of the South, who put down new roots in the state of Kansas.

Julie Denesha is a freelance multimedia journalist based in Kansas City. Contact her at julie@kcur.org.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.

See more, including more historic photos, at https://www.kcur.org/arts-life/2021-02-20/post-civil-war-photo-negatives-document-african-americans-building-new-lives-in-leavenworth.